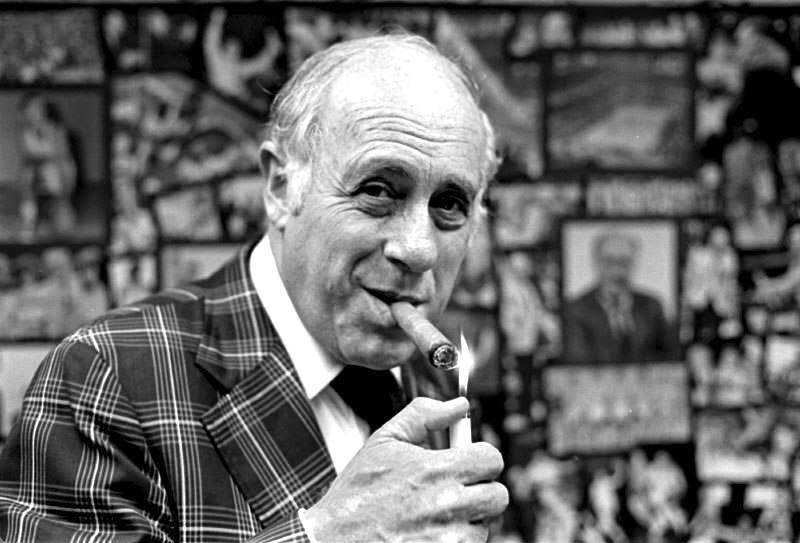

Red Auerbach, 1917-2006

Boston lost one of it’s true patriarchs this weekend. Arnold “Red” Auerbach passed away at age 89. He died of a heart attack, the Associated Press reported, according to an NBA source who did not want to be identified.

In two decades of NBA coaching, Auerbach won 938 games, a record when he retired in 1966, as well as a record nine NBA championship titles. In those 20 years, 16 with the Celtics, Auerbach had only one losing season while winning almost two-thirds of his games. Coaching the Celtics he won an amazing eight consecutive titles from 1959-66.

For all my years growing up on Boston, Red was the Celtics. He put together winning teams for almost 60 years. From Russell to Havlicek to Bird and beyond. Sixteen championships. He loved the team and the city, and the feeling was mutual.

I don’t think I can say it much better than Dan Shaughnessy of the Globe did:

For decades, he lit up our lives

By Dan Shaughnessy, Globe Columnist - October 29, 2006

We were so lucky. We had Red Auerbach for nearly 57 NBA seasons. We had his genius, his rough, old-school charm, and his Brooklyn-learned street smarts. And we lost him yesterday. At the age of 89. Just four days before the start of another Celtics season.

Red was the Celtics. Sure, we had Bill Russell, Bob Cousy, John Havlicek, Larry Bird, and the rest. But Red was the Celtics. He delivered 16 championships to our town. We never could pay back all the pride and glory he brought to Boston.

We tried. We dedicated a statue to Red a full 21 years before he died. We wrote books about him. We created a scholarship in his honor. We made documentaries about him and held a $500 per plate “Red-fest” at the Bayside Exposition Center.

“Most guys have to die to get a tribute like that,” Red said, with a chuckle.

We were hoping he never would die. As long as Red lived, there was still Celtic tradition, Celtic pride. We were looking forward to seeing him for one more opening night Wednesday at the Garden. It would have been his 57th opener with the Celts. It would have been his 61st opening night with the NBA, a magnificent career that spanned the entire history of the league. But he just missed. In the end, he never lived to see the first Celtic cheerleader. Probably the way he wanted it.

Where do we start now that Red is officially finished? Do we tell you that he made more great deals than any executive in the history of sports? Do we tell you that he was the best coach, then the best general manager? Do we tell you that he invented the end zone dance?

That’s right, boys and girls. You may think that opponent-baiting started with NFL wide receivers preening in end zones, but it all goes back to the 1950s and a short fellow in a jacket and tie with a rolled-up game program in his hand – lighting up a Hoyo de Monterrey – as he sat at the end of the bench watching his Celtics bring home another win. Red’s victory cigar was the original in-your-face taunt. Celtic rivals despised the gesture and even Red’s players dreaded the ceremonial stogie: It just made the other team mad. It made them play harder. Red didn’t care. He was enjoying victory, already thinking about the next game.

Red was decades ahead of his time. The old saying was that Red was playing chess while the rest of the coaches and GMs were still playing checkers. He outsmarted all of them. When confronted, he punched first and asked questions later. He dared his rivals to beat him. And none ever could. Drove them crazy.

Being Jewish helped. It taught him discrimination at a young age. This knowledge was handy when Red came into a fledgling league that was initially all white, but one day would be more than 70 percent black. Red was the first NBA executive to draft a black player, the first coach to start five black players, and he hired the first black coach (Russell) in the history of American sports. Russell, we all know, was more sensitive to frauds than any athlete on the planet. Russell went through walls for Red. And no one else.

Red was sometimes crude and ever vengeful. Ask Cedric Maxwell. When Max took too long to recover from knee surgery in 1985, Red shipped him out of town (for Bill Walton), then had all positive Maxwell references deleted from an Auerbach book that was still in production. Downright Kremlinesque. It took two decades for Red to agree to let the Celtics retire Max’s number.

He was well past 65 when he stormed across the parquet floor and challenged Moses Malone to a fight. A couple of years later, the death of Len Bias almost killed Red and sent the Celtics into a tailspin from which they still have not recovered.

What else can we tell you? Red was a sore loser and a gloating winner. Referees hated him. He got into beefs with the officials at old-timers’ games. Seriously. And he always hated Madison Square Garden, dating to the 1930s, when he felt his George Washington team was snubbed by the NIT.

Red loved “Hawaii Five-O.” He loved Chinese food and would order for the entire table. He was a historically bad driver, rarely getting into accidents, but leaving a trail of fenders and furious drivers in his exhaust. He collected letter openers from around the world and delighted in telling stories of deal-making with trinket merchants on other continents.

Red was constitutionally incapable of participating in small talk. He could be particularly ham-handed when dealing with women. In 1982, he barred Lesley Visser from the Celtic locker room just two years after attending her wedding in Boston.

In 1984, I brought my young wife and infant daughter to the NBA meetings in Salt Lake City. Red had given me a box of cigars when our daughter was born (probably a company violation to accept them, but hopefully the statute of limitations on graft has expired) and I was anxious to have him take a look at our 6-week-old baby. Red took one look at little Sarah, blew some smoke past my wife’s head, and said, “Lady, you got a lot of balls bringing that baby all the way out here. Yes, sir, a lot of balls.”

It took a while to explain to my wife that this was Red’s highest form of praise.

For all that bluster, there was a sweetness about him and you saw it when he was in the presence of his late wife, Dorothy, and his two daughters. In all the years he worked for the Celtics, Red never bought a house in Boston. Dorothy liked her native Washington and dutiful Red went along with the plan. Case closed.

Modern laws be damned, the Celtics should hand out cigars at the Garden opening night. After the anthem, before the opening tap, turn out the lights and let everybody light up a Hoyo de Monterrey. It’ll smell like victory.